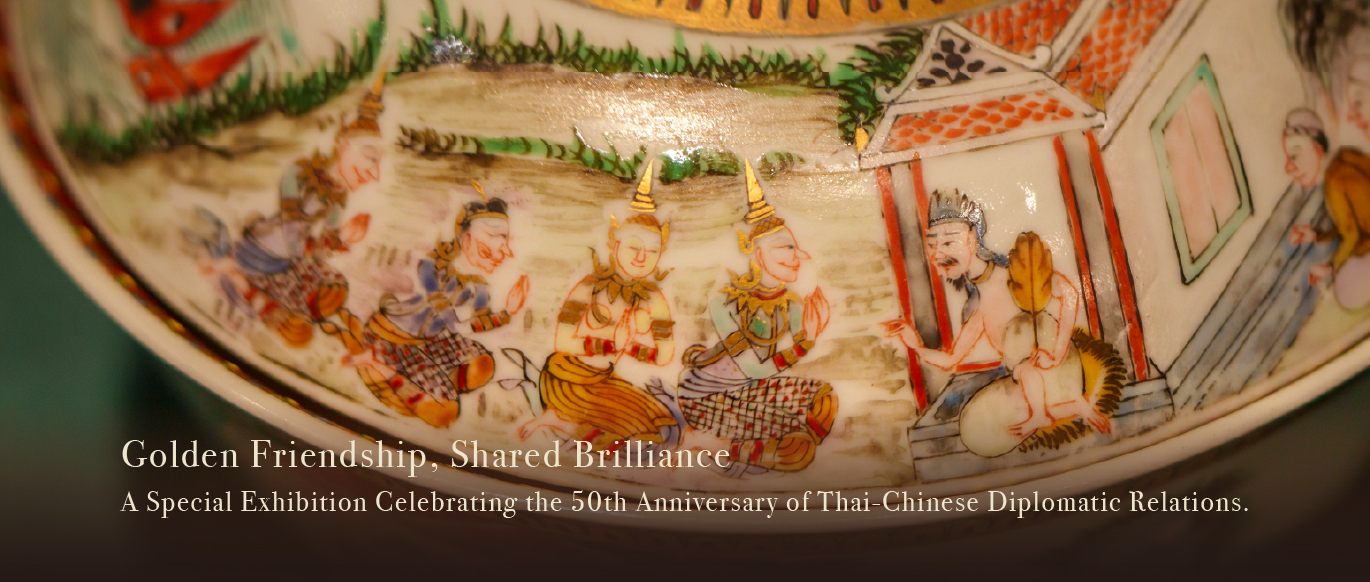

Exhibition Room No. 1: West Wing Gallery, Meridian Gate

Shanshui, or Chinese landscape painting, originated in China\'s Six Dynasties period (222–589 CE). By the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) it began to branch into two major styles of painting, namely blue–green shanshui and ink wash shanshui. Blue–green shanshui (literally ‘mountain–water\') painting was named for the use of blue and green mineral or plant dyes as primary colours, and it benefited during the Tang from the outstanding contributions of Li Sixun and his son Li Zhaodao, known as the ‘Two Lis\'.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), artists like Wang Shen, Zhao Lingrang, Wang Ximeng, Zhao Boju and Zhao Bosu, building on the achievements of the Two Lis, further developed the style, perfecting the expressive techniques of blue–green shanshui. They were followed in the early years of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), when Qian Xuan and Zhao Mengfu began exploring ways to integrate blue–green shanshui with the tastes and predilections of the literati. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, Qiu Ying, and other members of the Wu School made substantial progress towards a fusion of the blue–green and ink wash styles. Dong Qichang, a renowned painter in the late Ming, and the ‘Four Wangs of the Early Qing\' (Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui, and Wang Yuanqi) furthered the art form with their emphasis on imitating ancient techniques. In China\'s modern era, artists including Zhang Daqian and Huang Binhong brought about new breakthroughs, transforming this long–lasting painting style.

This exhibition highlights the important achievements and cultural significance of ancient Chinese blue–green shanshui painting, fostering audience in understanding Chinese shanshui painting and China’s national culture.

Dazzling Splendours: from the Eastern Jin dynasty to the Song dynasty

During Wei Jin and Six Dynasties, landscapes appeared primarily as a background to figure paintings. In the Tang dynasty, the blue–green and ink wash styles began to develop, and the blue–green shanshui works of Li Sixun and Li Zhaodao (the Two Lis) represent the gradual maturation of China\'s shanshui as a distinct painting style. Blue–green shanshui background paintings in the Tang–era murals at the Dunhuang caves show the considerable development of the technique in this period.During the Song dynasty, blue–green shanshui gradually developed into an art form in its own right, with Wang Shen and Zhao Lingrang incorporating the tastes of the aristocratic literati into their works. ‘A Panorama of Rivers and

Mountains\' by Wang Ximeng and ‘The Landscape in Autumn\', which is believed to be one of Zhao Boju\'s works, stand as typical masterpieces of the Song ‘Imperial Academy\' school. Both Zhao Boju and his younger brother, Zhao Bosu, created their own innovations based on the artistic style of earlier blue–green shanshui painting.

Dark Ink and Pure Tastes: from the Yuan dynasty to the Mid–Ming dynasty

In the early years of the Yuan dynasty, the blue–green shanshui paintings of Qian Xuan and Zhao Mengfu drew inspiration from Jin and Tang traditions, while embodying scholarly airs. During the mid–Ming era, painters of the Wu School contributed further by achieving a fusion of the blue–green style and the painting techniques and tastes of the literati. In addition, blue–green shanshui was also combined with other painting styles to illustrate scholarly life, including paintings on the theme of artists\' pseudonyms, ‘thatched hut\' paintings (depicting the studies of painters), travel paintings, and paintings of real landscapes. Artists such as Zhou Chen and Qiu Ying sought to integrate the styles of blue–green shanshui with that of the ‘Imperial Academy\' school, and in so doing demonstrated the tastes of the literati.

Exhibition Room No. 2: The Main Hall at the Meridian Gate

Featured Item: ‘A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains\'

The origin of ‘river and mountain\' paintings can be traced back to the Tang dynasty, when Wu Daozi painted a panorama depicting a three hundred li stretch (with li as a Chinese unit of length) of the Jialing River. By the Song dynasty ‘river and mountain\' paintings had been established as a distinct style. Two pieces in the Palace Museum collection, ‘A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains\' by Wang Ximeng and ‘The Landscape in Autumn\', attributed to Zhao Boju, fall into this category. Wang Ximeng’s ‘A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains\' is the archetypal work of the blue–green shanshui style, in which it stands as the most representable and historically marked piece. After acquiring Wang\'s masterpiece, the Qianlong Emperor in the Qing dynasty ordered the palace painters Wang Bing and Fang Cong to create two separate reproductions, which have also been included in this exhibition for comparison.

Long ‘river and mountain\' scroll paintings in the Ming and Qing dynasties followed the practice of earlier Song dynasty painters, demonstrating the painters’ expertise in depicting rolling and undulating mountains as well as their diversified painting techniques and stylistic forms.

Exhibition Room No. 3: East Wing Gallery, Meridian Gate

Imitations Surpassing the Originals: From the Late Ming dynasty to the Mid-Qing dynasty

During the late Ming era, Dong Qichang advocated the division of shanshui into Southern and Northern schools and promoted the use of Southern school painting techniques. When reproducing works by painters like Ni Zan and Wu Zhen, who were renowned for their ink wash prowess, Dong added blue and green colours. This reflects the guiding principle behind his creations: to emulate the ancient masters but not be held back by them.

The ‘Four Wangs of the Early Qing\' (Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui, and Wang Yuanqi), whose works formed the artistic mainstream of the early Qing dynasty, practiced and developed Dong Qichang’s theories. All four painters were accomplished blue–green shanshui masters, with Wang Hui and Wang Jian particularly successful. During the reigns of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors, at the height of the Qing’s prosperity, palace painters such as Tang Dai, Zhang Zongcang, Fang Cong, and Wang Bing were adept at blue–green shanshui techniques, and the blue–green style of painting became the preferred expressive form when creating landscape backgrounds for ‘The Southern Inspection Tour\', ‘Imperial Merriment\', and other works.

The New from the Old: the Modern Era

In the mid–nineteenth century, Shanghai, the affluent city in the lower Yangtze River region, became the centre of art creation in southern China. Blue–green shanshui works by early Shanghai School painters like Zhang Xiong and Ren Xiong inherited the traditions of scholarly paintings, but also exhibited an unconventional boldness and a sense of abandon. Blue–green shanshui painters active in Shanghai during the Republican Era included Wu Hufan, Zhang Daqian, Feng Chaoran, Wu Guxiang, and Zhao Shuru, while the Beijing painting circle boasted a number of artists proficient in blue–green techniques, such as Jin Cheng, Huang Binhong, Hu Peiheng, Xiao Xun, and Qi Kun. Together, these artists initiated a rebirth of traditional painting in the modern era.