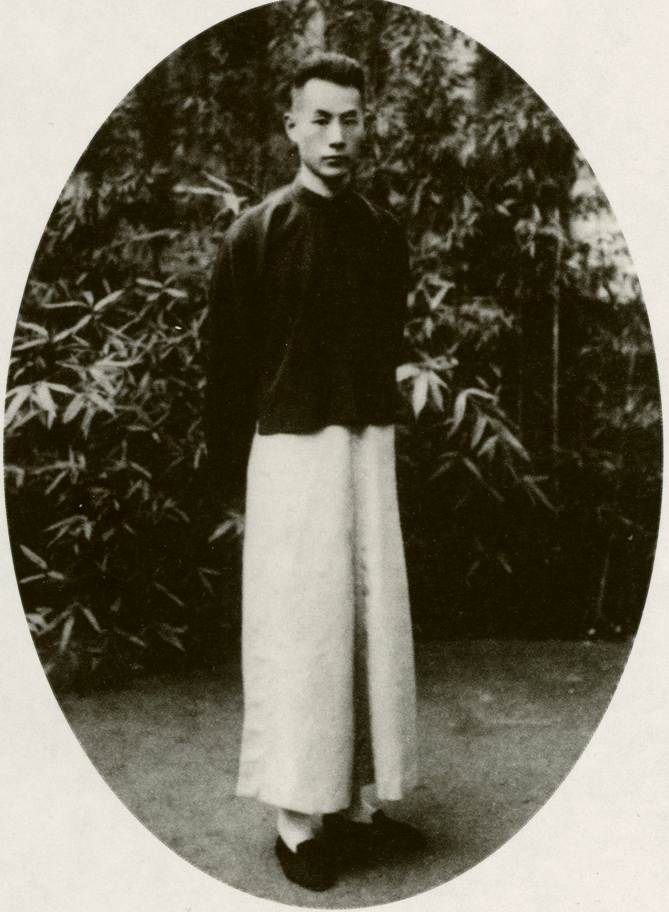

Zhang Boju (1898–1982) was a renowned art connoisseur and collector of ancient Chinese calligraphy and paintings. From Xiangcheng in Henan Province, his original name was Zhang Jiaqi, and he was later known by his courtesy name Congbi and his style names Chunyou Zhuren (lit. “Master of the Spring Excursion”) and Haohao Xiansheng (lit. “Sir Good Good”). He is regarded as one of the six great Chinese art collectors of the twentieth century. As one of the most outstanding cultural personalities of modern Chinese history, he is widely recognized for his achievements in calligraphy, poetry, opera, and related arts.

From the age of thirty, Zhang Boju began collecting Chinese calligraphy and paintings. With his discriminating eye, he was able to identify priceless works of art and add them to his collection. The oldest works in his collection included the “Precursor of Model Calligraphy” A Consoling Letter (Pingfu tie) by Lu Ji (261–303) of the Western Jin dynasty (265–316) and the oldest extant landscape Spring Excursion (Youchun tu) by Zhan Ziqian (mid–late sixth century) of the Sui dynasty (581–618). His preservation of this exceptional collection inspired Mr. Qi Gong (1912–2005) to say of him, “He is unprecedented among the ancients, and none will ever surpass him. He is the first among all other private collectors under heaven.”

His activities as a collector began as a hobbyist with an amateur interest, but his love for Chinese art eventually transformed into a personal undertaking to protect precious Chinese art from being traded overseas. This passion drove him to sell his family property to support his efforts. He is noted for saying, “That which I have collected does not need to remain in my possession, but it must remain eternally in our land throughout the generations.” This statement reflects his patriotic sentiments and reverence for ethnic causes.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Zhang Boju donated or transferred the ownership of the collection to which he dedicated his life to the new nation. The calligraphy and paintings from his collection remain an important part of China’s national treasury. As a testament to the continuity of China’s culture, these works preserve the essence of Chinese art and allow people from all walks of life access to the beauty they contain.

Zhang Boju is highly esteemed for his work as an art connoisseur and collector and for his protection of national treasures. He is also respected for his generosity. Through his donation, he took his private possessions and shared them with the public.

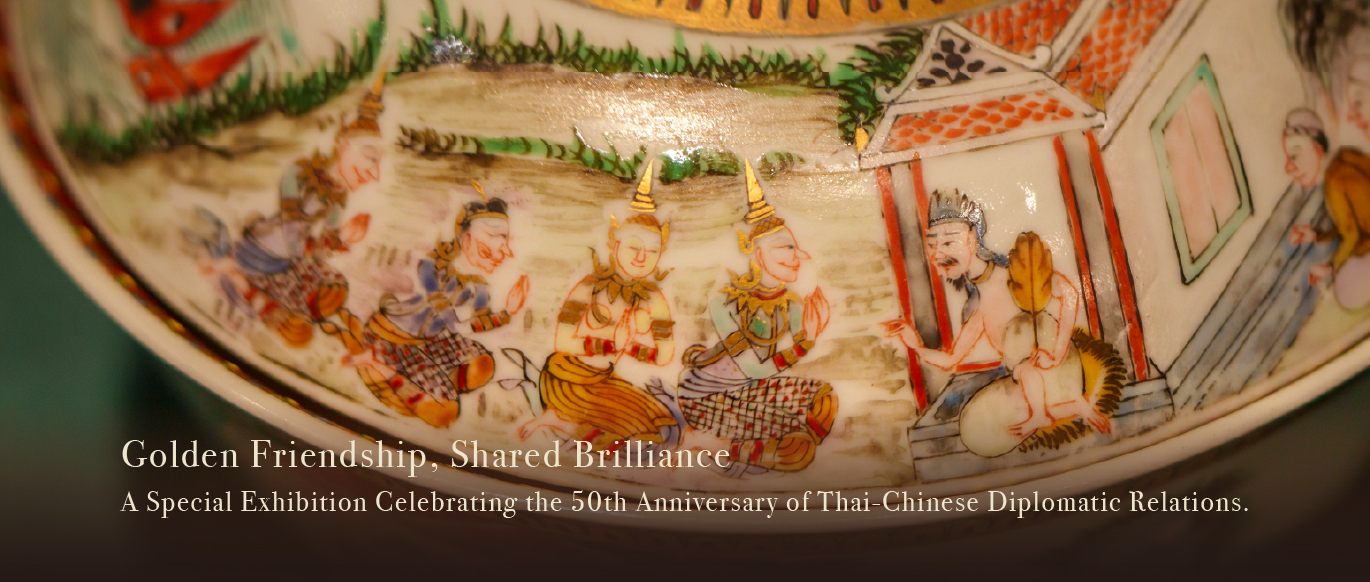

This year is the 120th anniversary of Zhang Boju’s birth. The Palace Museum, the Zhang Boju and Pan Su Cultural Development Foundation, the National Museum of China, and Jilin Provincial Museum jointly present this exhibition in honor of his life and contributions.

The exhibition features traditional Chinese paintings and calligraphy from state-owned museums including the Palace Museum, National Museum of China, and Jilin Provincial Museum. Respectively divided into three sections representing works from these museums, the exhibition displays artwork organized in chronological order in each section. The curators strive to offer a relatively comprehensive overview of Zhang Boju’s collection and connoisseurship through this impressive gathering of the collector’s works; indeed, thirty-three exquisite pieces or sets of paintings and calligraphy from his original collection are on view in the galleries.

Some of the most important pieces featured in the exhibition are replicas since the originals are currently being stored for conservation between limited occasions of exhibition. This measure is necessary to protect all ancient works of traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy due to their extreme vulnerability to environmental factors. The replicas in this exhibit include such works as A Consoling Letter by Lu Ji, Spring Excursion attributed to Zhan Ziqian, Zhang Haohao by Du Mu, and Encomium on Daoist Attire by Fan Zhongyan.

Works from the Donated Collection of Zhang Boju

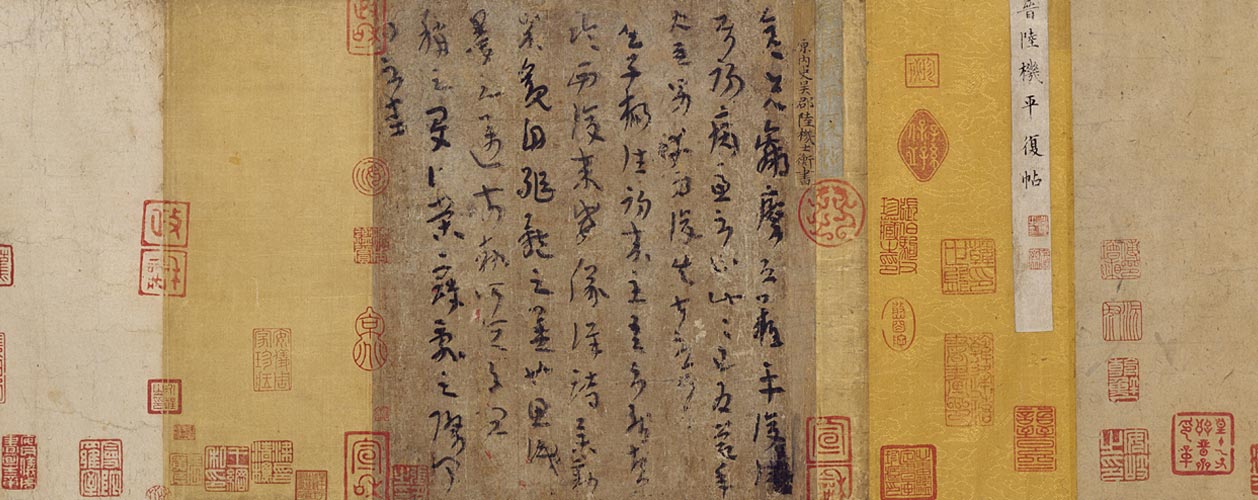

(Replica) A Consoling Letter (Pingfu tie) by Lu Ji (261–303) of the Western Jin dynasty (265–316) is the oldest extant work of model calligraphy. Having been authenticated by art historians, this work has been called the “Ancestor of Model Calligraphy.” The characters in this work are believed to be an important testament to the evolution of regular script from clerical script. With a distinguished and traceable provenance, this work of model calligraphy, the earliest of its kind, boasts an unrivaled status in all of Chinese calligraphic history.

(Replica) Spring Excursion (Youchun tu) is attributed to Zhan Ziqian (mid–late sixth century) of the Sui dynasty (581–618). The painting is a highly representative early example of landscape and is believed to have been accomplished by a pioneer of landscapes with gold and blue-green coloration (jinbi shanshui), a type further developed in the Tang dynasty (618–907). Although scholars debate who actually painted this work and when it was produced, the painting is a critical part of the history of Chinese landscapes.

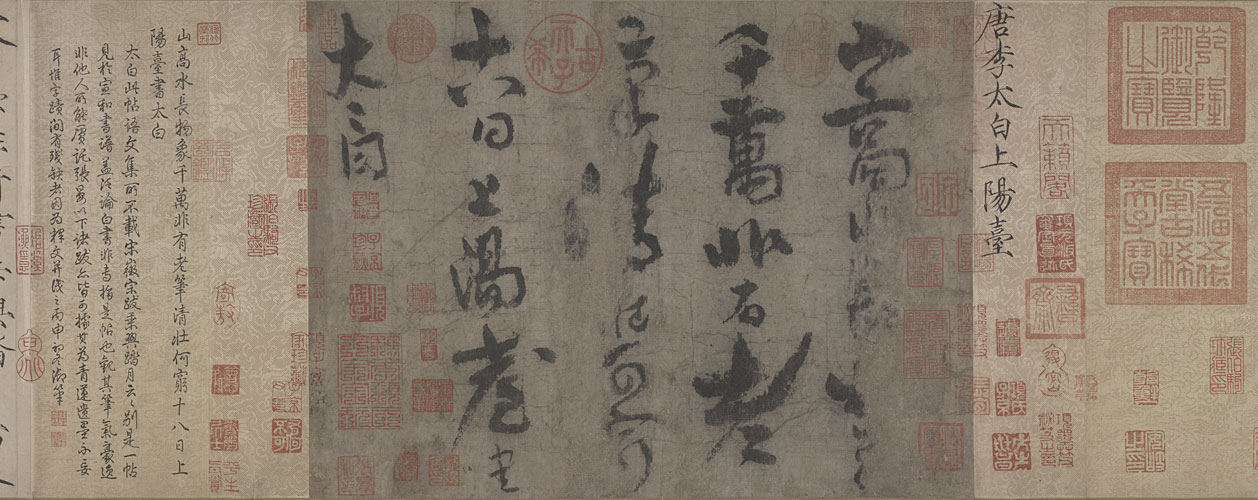

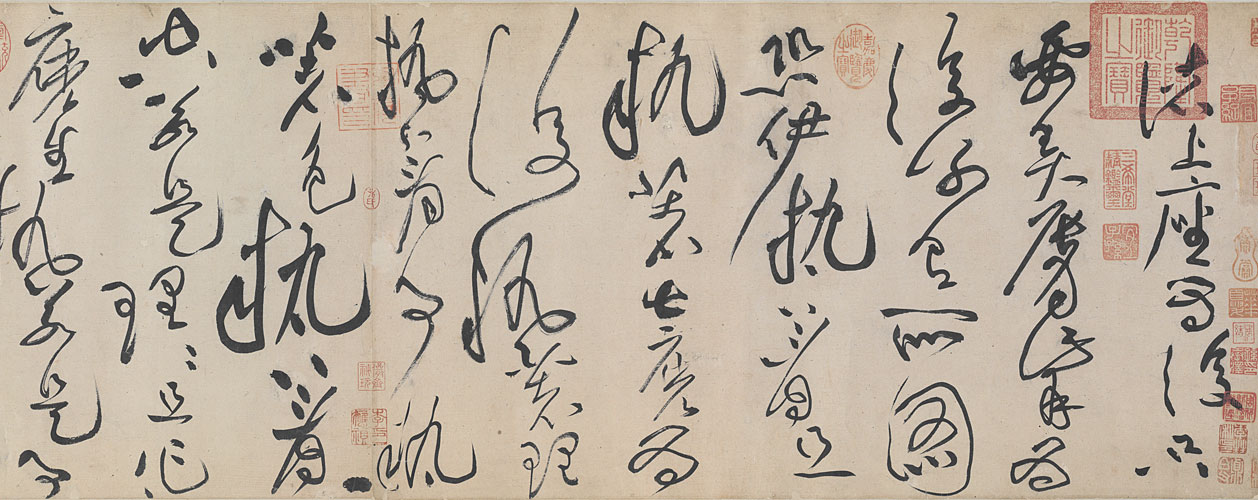

Ascent to Yangtai Temple (Shang yangtai tie juan, named after Yangtai Temple on Mount Wangwu) is believed by many scholars to be the only extant work by the “Immortal Poet” Li Bai (701–762). The characters in the work show the advanced proficiency of the poet’s calligraphic hand. As an irreplaceable national treasure, the work is significant beyond compare.

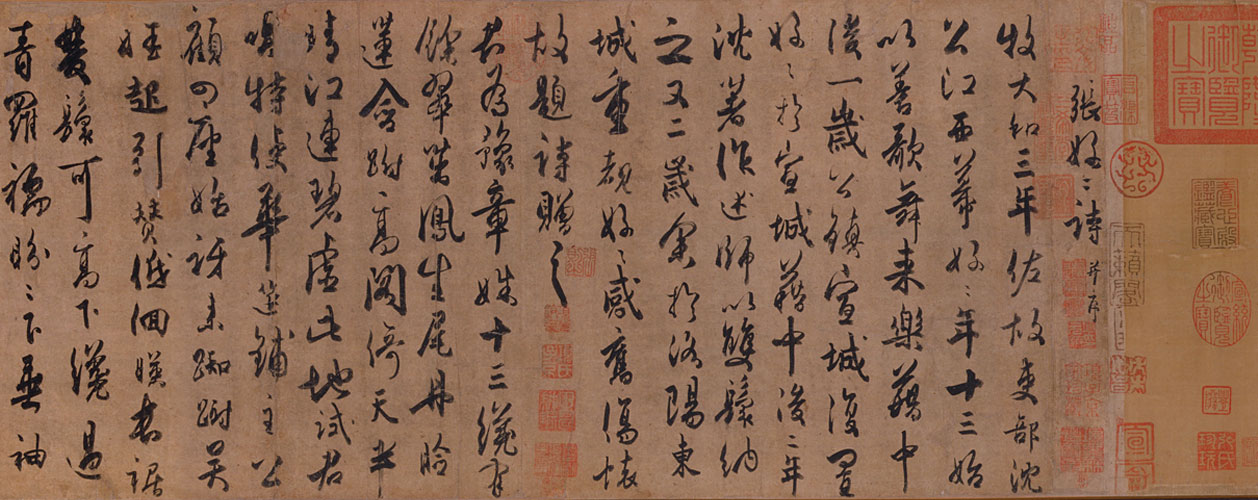

Zhang Haohao (Zhang Haohao shi juan) is a poem by the poet and calligrapher Du Mu (803–852) of the Tang dynasty (618–907). As the only remaining work by this artist, the work is one of few extant originals by Tang dynasty artists.

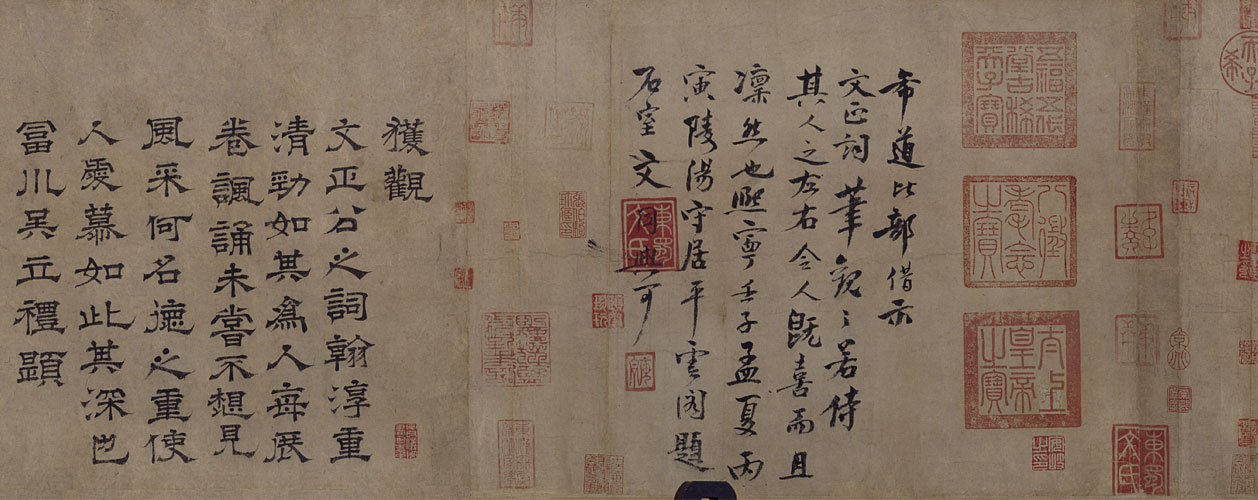

Encomium on Daoist Attire (Daofu zan juan) is by Fan Zhongyan (989–1052), an official and literatus of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). He wrote this piece in honor of the Daoist garb made by his friend Xu Yan, a secretary of Pinghai (present-day Quanzhou, Fujian Province). As one of only a few extant works by the artist, the encomium has been praised for its literary value and the aesthetics of the calligraphy.

Personally Written Poetry (Zishu shi ce) is an album by Cai Xiang (1012–1067), one of four celebrated Song-dynasty (960–1279) calligraphers. The artist was widely known for his calligraphy during that period and was promoted as the best calligrapher of the dynasty. This work features his flowing brush style. With each refined stroke, the piece reflects the developed style of Cai Xiang at middle age. In his Catalogue of Calligraphy and Paintings by Congbi (Congbi shuhua lu), Zhang Boju praises this work as the artist’s finest.

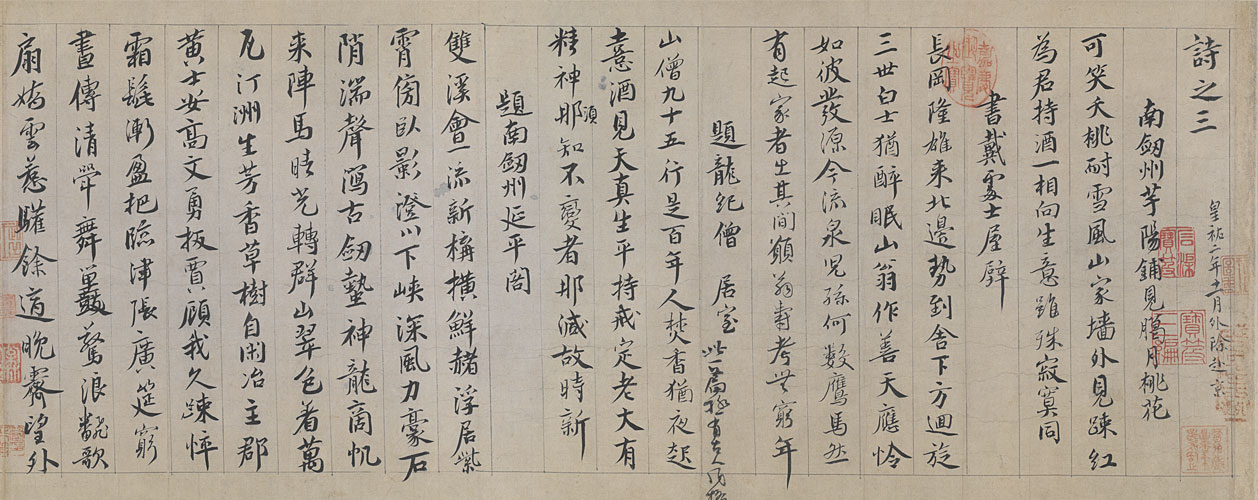

Miscellaneous Poetry (Zashi tie juan) in running and cursive script is a compilation of calligraphic works produced during the Song dynasty (960–1279) by Wu Ju (act. twelfth century), whose artistic contributions have been considered comparable to Mi Fu (1051–1107). The compilation comprises ten works of poetry by earlier artists in the running and cursive script of Wu Ju. Originally written on ten pieces of paper, the works were later combined and mounted as six unrelated segments on a scroll; some of the original content has been lost. The variation in the stroke-style used to write the characters in these pieces show deliberate aesthetic choices by the artist. The style is lively and natural and resembles that seen in the calligraphy of Mi Fu. Wu Ju’s proficient hand is evident in the distribution of strokes and other features of the compositions in which he harmonized uneven aspects with regularity. His style is distinct from Mi Fu’s more intense and densely constructed style. This compilation was acquired by Zhang Yingjia (act. seventeenth century) during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and later by Zhang Boju, who with his wife Pan Su (1915–1992) donated it to the nation in 1956.

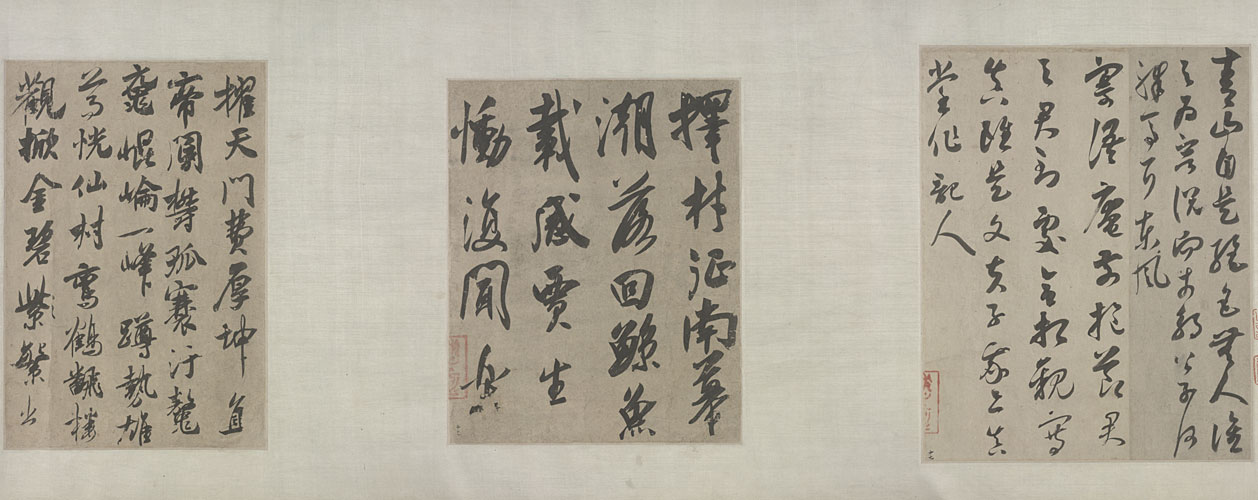

The Host of Monastic Superiors (Zhu shangzuo tie) is a masterpiece in cursive script by Huang Tingjian (1045–1105), who was one of four celebrated calligraphers of the Song dynasty. Zhang Boju records in his Catalogue of Calligraphy and Paintings by Congbi (Congbi shuhua lu) that since the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) this piece was considered Huang Tingjian’s best work. The work has a unique aesthetic and reflects an artistic style unrestrained by traditional conventions. The artist skillfully hovered his wrist above the page as he wrote with his idiosyncratic technique.

Homeward Bound on a Snowy River (Xuejiang guizhuo tu) is a landscape painting by Zhao Ji (1082–1135), also known by his imperial temple name Huizong (r. 1100–1126). Zhang Boju praised the work for its dense arrangement and extraordinary brush style. The work is a fine example of the advanced artistic proficiency of the court painting academy during that emperor’s reign.

One Hundred Flowers (Baihua tu juan) is believed to have been painted by an artist named Yang Jieyu, a woman of the Liu Song dynasty (420–479). This work is appraised in the first edition of Precious Collection of the Stone Moat (Shiqu baoji, chubian) as a notable piece from China’s successive dynasties. Her work is the earliest known work of extant art by women painters. Zhang Boju noted the work was by a woman artist and that it had been considered a rare work since the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties. The scroll is currently in the collection of Jilin Provincial Museum.

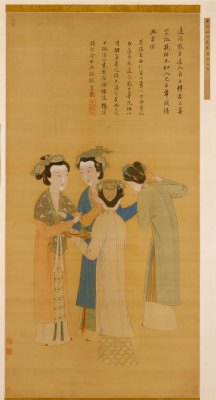

Palace Entertainers in the Kingdom of Shu (Wangshu gongji tu zhou) is a painting by Tang Yin (1470–1524, courtesy name Bohu), one of the four celebrated painters of the Wu school. The work was painted using an orderly technique (called gongbi) and a heavy use of color. The four women entertainers in the painting are clearly delineated in this work that displays the advanced brush techniques and overall artistic prowess of the artist.

Compendium of Calligraphic Forms for Discrimination (Huicao bianyi ce) is an album of work produced in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) by Ma Xiongzhen (1634–1677), who was known by his courtesy name Xibo and style name Tangong and served as a bannerman of the Bordered Red Banner. His father Zhang Mingpei progressed in official status after he had served the Manchu army as it advanced south of the Shanhai Pass during the campaign to establish the Qing dynasty in 1644 and its rule over China Proper. In 1656 (the thirteenth year of the Shunzhi reign, 1644–1661), Ma Xiongzhen was appointed by virtue of hereditary privilege as a vice-administrator in the Ministry of Works. Having also served as a left assistant-censor-in-chief and an academician of the Palace Historiographic Academy, he was appointed as the governor of Guangxi in 1670 (the ninth year of the Kangxi reign, 1662–1722). When Wu Sangui (1612–1678) rebelled against the empire, Ma Xiongzhen was imprisoned by the insurgent General Sun Tingling (d. 1677) and died as a martyr. He was honored with the posthumous name Wenyi (lit. “Cultured Resilience”). During his captivity, he produced this work (Compendium of Calligraphic Forms for Artistic Discrimination, Huicao bianyi ce), which he modeled after Compendium of Characters (Zi hui) by Mei Yingzuo (act. late-sixteenth to early-seventeenth century) of Xuancheng, Anhui Province. Listed vertically in columns, each character in this work was carefully written in various styles; although, some characters have more representation than others. The smaller regular script characters beside the primary columns were written by the artist’s secondary wife Gu Quan (act. early Qing dynasty). Never published, the work was taken by the artist’s aides when fleeing and delivered, along with another work (Huji lou yigao, translation uncertain), to his son Ma Shiji, who preserved them for posterity. In 1771 (the thirty-sixth year of the Qianlong reign, 1736–1795), the musical-dramatist Jiang Shiquan (1725–1785) in his Guilin Frost (Guilin shuang) wrote of Ma Xiongzhen’s experiences in Guangxi; in the part entitled Explanations of Calligraphy (Shi tie), he writes about how Gu Quan added the smaller characters. This album was a part of Zhang Boju’s older collection and in it he added two colophons, one in 1958 (the wuxu year) and the other in 1960 (the gengzi year). In 1963, he donated it to the National Museum of Chinese History (now called the National Museum of China).

Apart from the masterpieces outlined above, Zhang Boju donated many works by Zhao Bosu (1124–1182) of the Song dynasty (960–1279); Qian Xuan (1239–1301), Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), Zhao Yong (act. early fourteenth century), and Wang Mian (act. fourteenth century) of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368); Shen Zhou (1427–1509) and Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644); Jiang Tingxi (1669–1732) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911); and many other calligraphers, painters, and artists of important artistic schools.

Translated and edited by Adam J. Ensign and Zhuang Ying