His Highness Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani is both an eminent member of the Qatari royal family and a distinguished collector. With a keen eye, he has collected rare treasures from all over the world. This collection includes relics thousands of years old from Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, fine artworks from the medieval Islamic world, and Indian jewelry from the reign of the Mughal Dynasty, and is characterized by its exceptional diversity, abundance and exquisiteness. But for His Highness's great resources, solid expertise, and many years' unremitting commitment to and obsession with art, it would be absolutely impossible to see so many rare treasures in one collection. I admire His Highness for his generous commitment to collection, and I greatly appreciate the history, crafts, beliefs and beauty embodied in his collected treasures.

These ingeniously crafted, uniquely designed artefacts distinguish themselves not merely by their luxurious materials, but, more importantly, by the spiritual strength by which they move the onlooker. These collected treasures have amazed me; whatever the period or ethnic group, over thousands of years humans have striven to transform the endowments of nature into highly creative works of art through their intellectual work, and thereby to attain perfection. It is safe to say that humanity has never slackened in its near-crazed quest for beauty, and its mastery over beautiful works has reached superb heights.

The Al Thani Collection is like a series of windows linking the past and present, allowing those of us in the present to see cultural landscapes that have been lost in the depths of history. Artefacts from Sumer, Egypt, Persia, Greece and Rome form a miniature landscape of ancient civilizations, and shed light on mysteries known to few. Different peoples have marked these relics with their own styles, which reflect the unique sources of each culture but strike the viewer with an equally powerful charm. There is a wide range of cultural relics from the medieval Islamic world, such as astrolabes, candle stands, Qur'ans and miniatures, all testifying to Muslims' devoutness and ingenuity and bearing witness to the past glories of the Arab, Ottoman and Mughal empires. There are also luxuries from European countries, whose elaborate craftsmanship reflects the European noble's pursuit of a pleasurable, luxurious life and represents the extraordinary achievements of commercial civilization as it matured and improved day by day. Indian jewelry is another major category within the Al Thani Collection. These items are physical embodiments of the Indian Maharajas' aesthetic tastes over the centuries: the elaborate decorative styles and lustrous and dazzling gems, whether delicate or heavy or bold, have established a lively Southern Asian style, enabling the viewer to see the aesthetics and techniques of India under the reign of the descendants of the Mongols, as well as the Westernizing tendencies brought by British colonization. Herein lies the most outstanding value of The Al Thani Collection: the items embody history while being full of life, and they call for a tolerant, open mind and a mutual respect for the achievements of each other's cultures.

The Palace Museum has always had this kind of open mind. It is not only a treasury of traditional Chinese culture, but also a beautiful palace that attracts and displays fine cultural achievements from all around the world. With an international perspective, embracing diversity, we have been actively promoting Sino-foreign cultural exchanges, unwilling to miss any outstanding resource of art. We are committed to enhancing communication and mutual understanding between China and the world while broadening Chinese people's horizons. In the late spring and early summer of 2018, the Palace Museum will cooperate closely with His Highness Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani to hold at the Meridian Gate Treasures from The Al Thani Collection, an exhibition centered on His Highness's collection. It is my hope that both Chinese and foreign visitors will appreciate the splendid, crystalline beauty, the fine, elaborate craftsmanship, and the profound cultural significance of these items, gaining pleasure and satisfaction from this luxurious visual feast. I have confidence that in the majestic Forbidden City The Al Thani Collection can be displayed to the best possible effect!

Shan Jixiang

Director of the Palace Museum

Featured Objects:

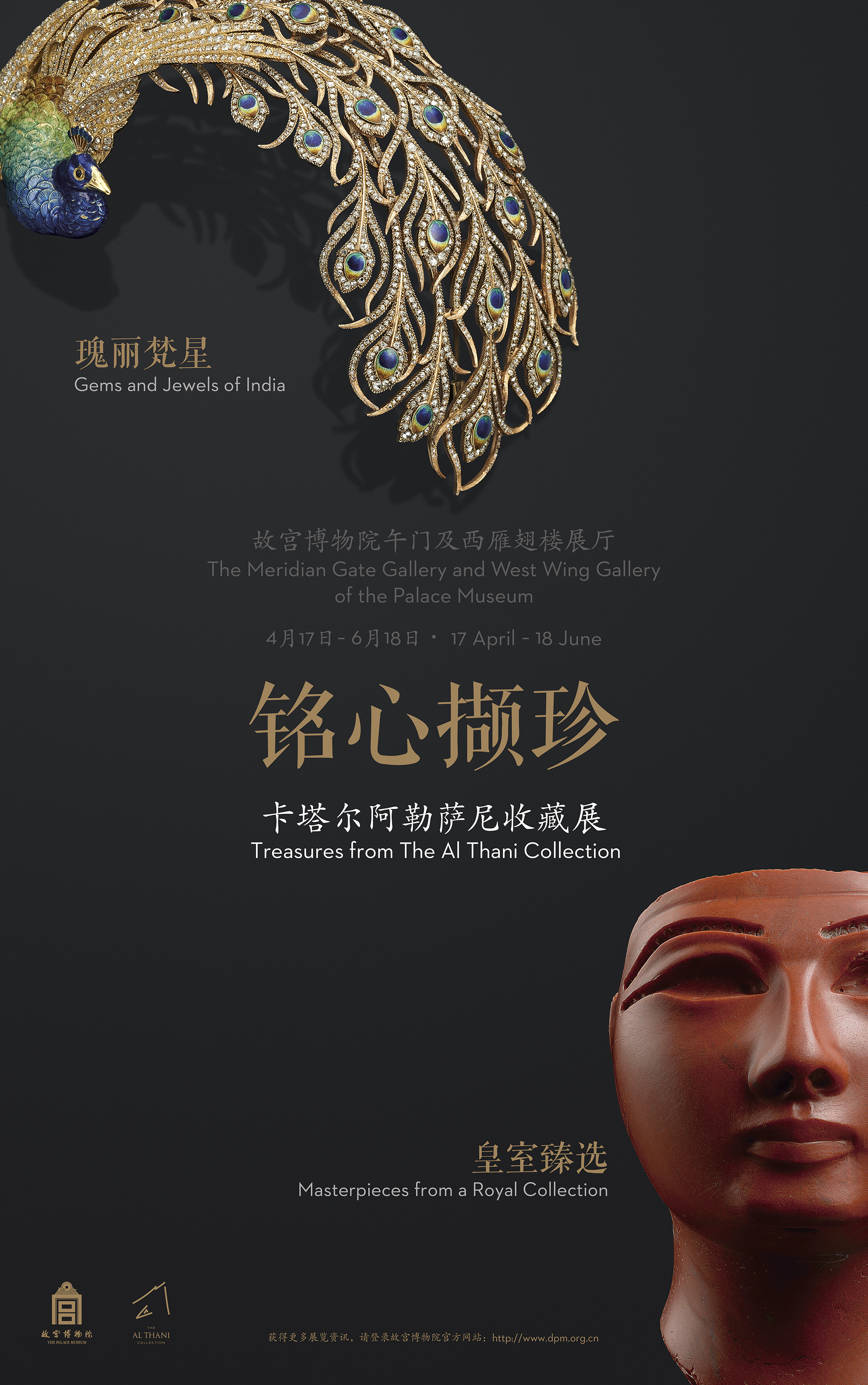

Aigrette

Mellerio dits Meller, Paris, 1905

Gold, platinum, diamonds, enamel

H 15.5 cm, W 6 cm

Provenance: Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala

Used by Mellerio dits Meller since 1867, the peacock motif provided the opportunity of combining blue and green, something rather unconventional in European jewellery of the day. An ardent Francophile, Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala bought this aigrette while in Paris in 1905, and it is visible in portraits of his young European wife, Anita Delgado, whom the ruler met in 1906 when he went to Spain for the wedding of Alfonso XIII.

Head of a Royal Figure

Egypt, 1473–1290 BC

Red jasper

H 9.6 cm, W 6.1 cm, D 7.5 cm

Provenance: Simon Ohan Simonian, Cairo, until 1977; private collection, Paris, 1977; Christie’s, New York, 7 December 2011 (lot 35)

Although the upper part of the head is missing, this tiny portrait can be considered a sculptural work of art in itself. The head is carved from a piece of red jasper of homogenous colour and is cut off directly over the eyebrows by a smooth, raised band belonging to the lower edge of a crown. The construction of the head makes it possible to conclude that it originally bore a blue crown probably of faience, as this headgear’s characteristic semicircular temple aps have the same shape as the line of the jasper head’s upper edge. This confirms the identification of the head as a royal image. A beard, probably of bronze, would have been fastened onto the chin. The head was set upon the shoulders of a statue with the use of a dowel and fastened with whitish mastic, also employed to attach the crown. The lower edge of the neck, rising ever so slightly, shows that a jewelled collar had once sat over the shoulders, allowing the artisan to cleverly bridge the transition from the head’s red stone to the material of the statue itself – either stone, wood or bronze.

Jasper, an opaque crystalline type of quartz or chalcedony, is available in red, green, yellow and brown variants. It was found incorporated in metamorphic rock, in the mountains of the eastern desert between Qena and Quseir. The bright red jasper, which owes its colour to the high concentration of iron oxide, was called hnmt in ancient Egyptian. It has been used since prehistoric times for the manufacturing of jewellery beads and occasionally for small vessels. In the New Kingdom, jasper was a popular material for hair rings inserted into braids, for scarabs, finger rings and jewellery. Since the time of Queen Hatshepsut (r. 1479–1458 BC), jasper was also used for carvings in the round. A small lion’s head of red jasper bears her name. In the pre-Ramesside temple at Medinet Habu, on the West Bank of Luxor, built under Hatshepsut, a nose and thumb of red jasper were found; a hand of the same material and in the same scale, also found in Medinet Habu, might belong to the same statue. Apparently, the areas of the statue showing naked skin were made of the red stone, which, according to the norms defined in Egyptian art, corresponded to a man’s skin tone. Since Hatshepsut had represented herself as a male pharaoh, red jasper could also have been used for her own gures.

Due to its missing inlays, dating the head is problematic. The empty, slightly tilted almond-shaped eyes appear over-large and give the face a mask-like expression. The profile views give a more objective image and can be compared not only with works in the round, but also with relief images, dated by their attendant inscriptions. A critical stylistic analysis favours a dating around 1475–1450 BC in the middle of the 18th Dynasty, in the time of Queen Hatshepsut or King Thutmosis III. However, deciding between the two rulers is difficult: Hatshepsut and Thutmosis were co-regents and are shown side by side in temple reliefs such as in the Chapelle Rouge in Karnak; only the inscriptions differentiate between the two rulers, who show neither typically male nor female traits. Hatshepsut, who administered the kingdom’s affairs for her young stepson Thutmosis, had herself depicted no longer as a woman but as a male pharaoh shortly after her accession to power. Therefore, a man’s red skin tone and beard do not speak against an attribution of this head to Hatshepsut. The overall expression of the features seems to be more feminine than masculine.

Even if a precise dating is not possible, this head is still of significant importance as a composite gure from the pre-Amarna Period, as are its perfect state of preservation and its artistic quality, earning it a privileged place among the sculptures of the New Kingdom. [Dietrich Wildung]