The Palace Museum and Beijing Fine Art Academy jointly present the exhibition "Prosperity in Tranquility: The Art of Qi Baishi" at the Forbidden City in the galleries of the main tower and western wing tower at the Meridian Gate (Wu men). The exhibition features over 200 paintings, seals, and literary works by the artist Qi Baishi (1864–1957) and is divided into four sections: Diligence Rewarded by Heaven, Dreaming of Home, Increased Ambition with Age, and The Art of Seal Engraving. The gallery in the main tower gallery atop the Meridian Gate will be open until 12th August while the sections in the western wing will remain open until 8th October. This exhibition is presented in tandem with an exhibition of Qi’s art at the Art Museum of the Beijing Fine Art Academy from 20th July to 23rd September.

The opening ceremony for the exhibition was attended by Party-Secretary Liu Baohua, Deputy-Director Wu Hongliang, and Deputy-Director Du Junshan of the Beijing Fine Art Academy; Deputy-Gallery Director Zheng Zhiwei of the Art Museum of the Beijing Fine Art Academy; and Director Shan Jixiang, Deputy-Director Wang Yamin, and Deputy-Director Lou Wei of the Palace Museum.

Pigeon (1952), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

Ambassador of Peace

In 1956, the nonagenarian patriotic artist received the International Peace Prize from the World Peace Council. He appeared in a photo with Premier Zhou Enlai (1898–1976) and painted the work Increased Longevity, Extended Years (Yishou yannian) for Chairman Mao Zedong (1893–1976). With a great desire for international cooperation, he produced works such as Peace (Heping) and Prosperity in Tranquility (Qingping fulai).

Increased Longevity, Extended Years with Chrysanthemums (1951), The Palace Museum Collection

Diligence Rewarded by Heaven

Qi Baishi had a square seal with the inscription “Behold, the Way of Heaven Rewards Diligence” (Yaozhi tiandao chou qin), which served as a personal exhortation and is now understood as revealing diligence as the artist’s secret of success. The driving force behind his diligence was his love for art.

Certain implications can be seen within his art and inscriptions. In his inscription on a work called Pumpkin, he describes how the preceding day strong winds prevented him from painting but how he made up for the lost time the following morning. He never rested from his art. His students recall how Qi never took a day off from painting. He only rested on two occasions—the day his mother passed away and that day of the violent winds.

Pumpkin (Undated), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

Born into a peasant household, he was trained as a carpenter and learned diligence from an early age. As he moved on into the world of art, he applied himself to studying the works of earlier artists. As he pursued his artistic endeavors, he endured the initial period of his work as a starving artist in the capital when he felt personally defeated for not attaining to the expectations he had for himself. Nevertheless, he did not seek pity from others. Indeed, he resolved to improve his work and achieve his dreams. As he applied the techniques of Xu Wei (1521–1593), Chen Chun (1483–1544), Zhu Da (1626–1705), and Shitao the monk (secular name Zhu Ruoji, 1642–1707) as foundational in his artistic development, he incorporated aspects of the Shanghai school of painting from studying the work of artists like Zhao Zhiqian (1829–1884) and Wu Changshuo (1844–1927). After a formative decade, he developed his own style and pioneered an artistic lineage known as Red Flowers with Ink-Black Leaves (Honghua moye). His exploration and innovation driven by diligence through hardship is an underlying theme throughout Qi’s life and provided fertile ground for his artistic achievement.

Shrimps (Undated), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

Living Beings

The Doctrine of the Mean (Zhongyong) expresses how the superior man develops his virtuous nature and studious inquiry by “seeking to carry it out to its breadth and greatness, so as to omit none of the more exquisite and minute points which it embraces” (translation by James Legge). Buddhist teaching includes the idea of “a world within a blossom and Heaven within a blade of grass,” that is, a heart free of everything may perceive a blossom or a blade of grass as Heaven. By achieving this awareness, the entire world is as empty as flowers or grass. All things small or great, expansive or diminutive, become a universe in and of themselves.

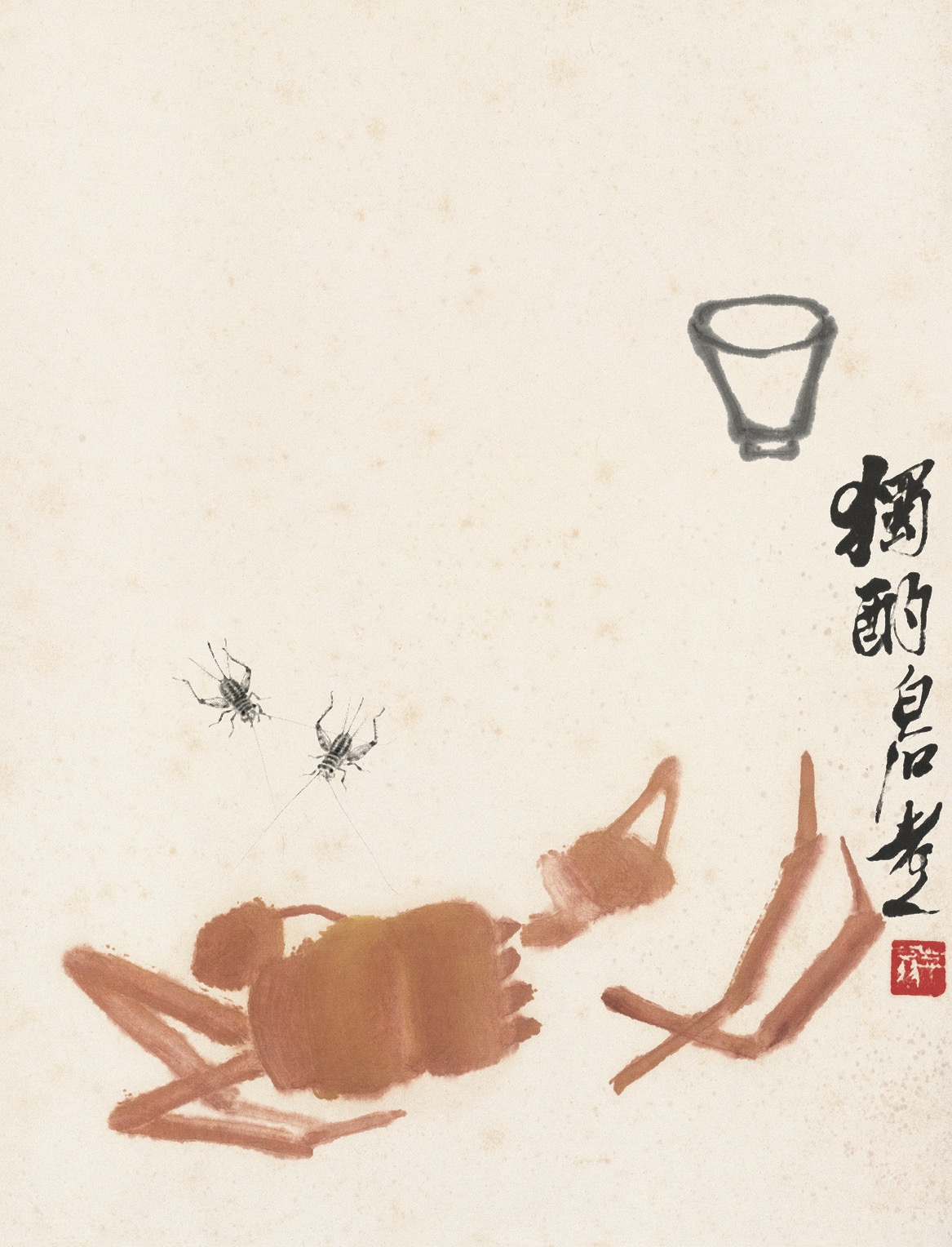

Qi Baishi’s paintings of plants and animals demonstrate the philosophic realm informed by this awareness of temporal matters and reflects the emotional focus of Chinese art. His painting Ignoble Life in the Grass (Caojian touhuo) expresses his sentiments regarding life in a chaotic world. Oil Lamp and Moth (Youdeng feie) reveals his deep compassion for the weakest creatures. It may be said that Qi’s paintings of plants and small creatures expressed his inner world and his reactions to life.

Drinking Alone (1949), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

Dreaming of Home

After settling in Beijing, Qi took inspiration from reminiscing about his previous life in the countryside. The benefits of living in the capital allowed him to succeed, but he never forgot his rural home with ancestral graves, family members, and childhood memories. He also remembered the sights and sounds of the natural surroundings he had left behind. His longing for home is evident in his poems, paintings, and seals.

Increased Ambition with Age

As Qi Baishi grew older, his love for his rural home, the country of his ancestors, and all living beings continued to expand. This deep-seated passion is apparent in his art. His love for his country and for people throughout the world and his artistic achievements earned him the award and title The People’s Artist. The ancient Chinese believed that one’s resolve and ambition should strengthen with age. Qi Baishi continued his artistic endeavors into old age. His life of passionate expression earned him recognition as a celebrated artist of the highest degree.

One Must Learn as Long as One Lives (Seal), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

The Art of Seal Engraving

Like all well-rounded traditional Chinese artists, Qi Baishi (whose style name Baishi means “White Stone”) developed a diverse range of skills in poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal engraving. During his artistic career, he never ceased engraving seals and earned his personally ascribed style name Prosperous Gentleman of Three Hundred Stone Seals. Although the exact number of his seals is unknown, Qi noted in the preface to his Seal Drafts by Baishi (Baishi yincao zixu) that he engraved over 3,000 seals after settling in Beijing after the age of fifty-five. The Beijing Fine Art Academy collection has 300 seals by the artist.

Prosperous Gentleman of Three Hundred Stone Seals (Seal), Beijing Fine Art Academy Collection

In 1954, the Palace Museum held a widely acclaimed exhibition on Qi Baishi's paintings at the Palace of Celestial Favor (Chengqian gong). The new exhibition sixty-four years later would be a feast for enthusiasts of Qi's art.

Translated and edited by Adam J. Ensign and Zhuang Ying