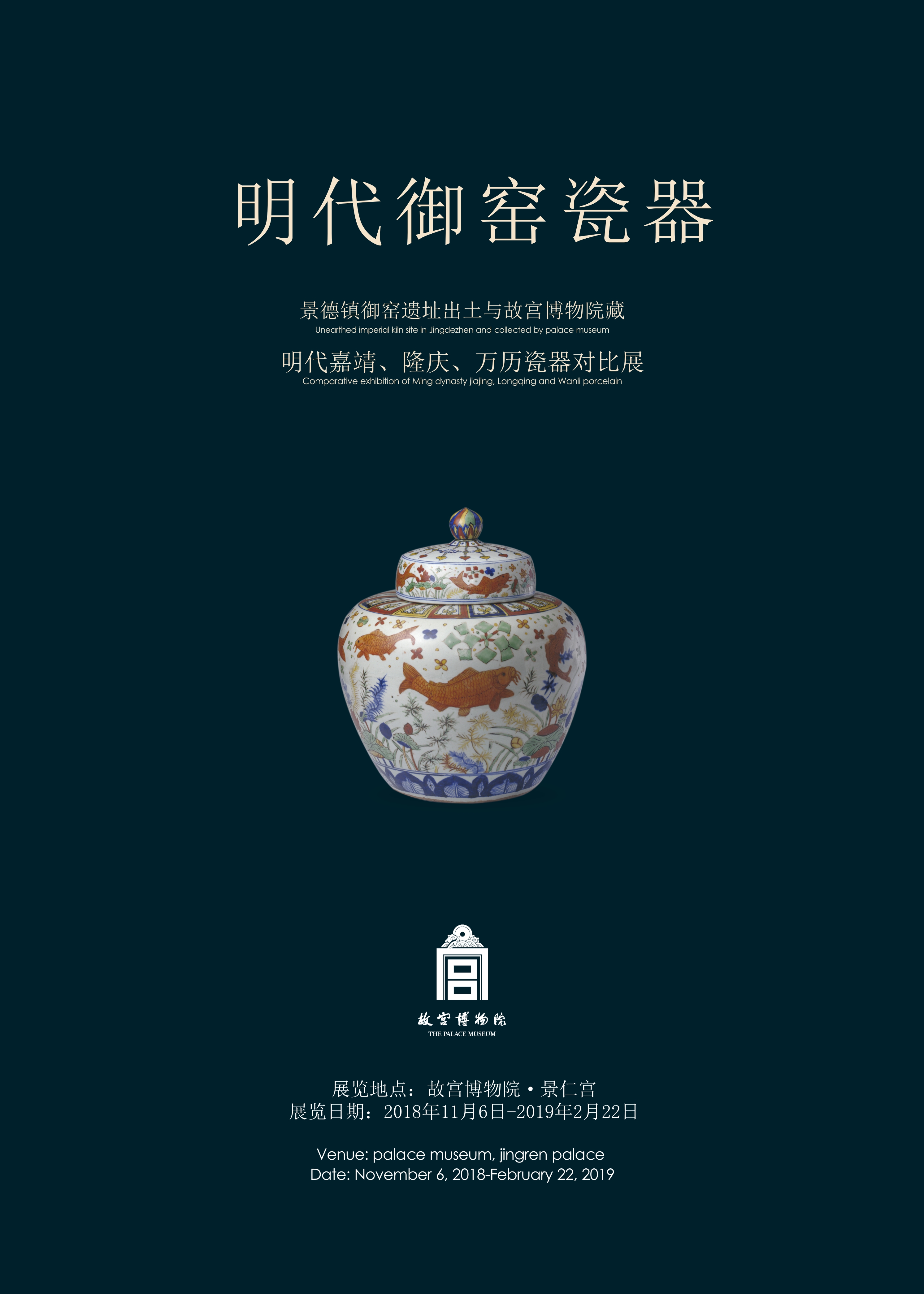

6 November 2018—The Palace Museum and the municipal government of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi Province) jointly present “Ceramics of the Ming Imperial Kilns: Comparing Ceramics Unearthed at the Ruins of the Imperial Kilns of Jingdezhen and Ceramics of the Jiajing, Longqing, and Wanli Reigns in the Palace Museum Collection” at the Palace of Great Benevolence (Jingren gong) in the Forbidden City.

In 2014, the Palace Museum and the Jingdezhen government signed an agreement which included a series of joint exhibitions of ceramics produced by the Ming (1368–1644) imperial kilns. From 2015 to 2017, the two parties organized five exhibitions featuring the following groupings: the Hongwu (1368–1398), Yongle (1403–1424), and Xuande (1426–1435) reigns; Chenghua (1465–1487) reign; Hongzhi (1488–1505) and Zhengde (1506–1521) reigns; Zhengtong (1436–1449), Jingtai (1450–1457), and Tianshun (1457–1464) reigns; and Ming and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. The current exhibition is the sixth and final of this series and features works from the Jiajing (1522–1566), Longqing (1567–1572), and Wanli (1573–1620) reigns.

Beginning in the 1970s, archaeologists found scattered ceramic shards while exploring the ruins of the Ming imperial kilns at Zhushan in Jingdezhen. Excavations conducted since the 1980s have resulted in abundant finds that have served to complicate scholarly understandings of Ming ceramics and various aspects of kiln production. The series of exhibitions has showcased a selection of fragments and restored works from Jingdezhen alongside some of the finest pieces from the Palace Museum collection.

This current exhibition is divided into three sections. Section I is entitled “Radiant Beauty” and features blue and white ceramics with white or yellow grounds or with added vitriol red. Section II is “Pure Elegance” showcasing ceramics with single-colored glazes. Section III is “Colorful Profusion” with a range of variously-colored, contrasting-color, polychrome, and red-green ceramics. While most of the works on view are from the imperial kilns and made during the aforementioned reigns, the exhibition also includes several examples of ceramics made in privately operated kilns.

The works on view demonstrate the unique characteristics of each of the three periods featured in the exhibition. During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (Zhu Houcong, 1507–1567), ceramic production increased rapidly at the imperial kilns. Many sacrificial vessels and large-scale works were produced in a variety of designs, including popular patterns and those associated with Taoism—of which the Jiajing Emperor was a zealous adherent. Subsequently, the Longqing Emperor (Zhu Zaihou or Zaiji, 1537–1572) oversaw a short but fruitful period of ceramic production; extant records and ceramic works from his reign show a reduction in the assortment of designs when compared to the preceding reign.

Due to the turbulent political climate during the reign of the Wanli Emperor (Zhu Yijun, 1563–1620), ceramic production declined in quantity and quality. The operations of the imperial kilns deteriorated into a crisis and operations eventually ceased in 1608 (the thirty-sixth year of that reign). Consequently, private kilns flourished for several decades until the fires of the imperial kilns were reignited in 1681—the twentieth year of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662–1722) of the Qing dynasty. (Some scholars argue that the restoration did not occur until 1683.) The ceramics produced during the Wanli period essentially show a continuation of aesthetic trends of the Jiajing and Longqing reigns. Since the Longqing Emperor lifted the isolationist ban on maritime trade, many ceramics produced by private kilns during the Wanli reign were sold overseas.

Translated and edited by Adam J. Ensign and Kang Xiaolu